In a lot of ways, it’s easy to put me in an ideological box. I’m a radical, anti-capitalist, intersectional, Black-feminist millennial– basically, as far left as you can get. As such, at the beginning of my licensure program, I naturally aligned myself with the educational left. I steeped myself in twitter groups such as #disrupttexts and tweeted “let kids read what they want!”. I was a progressive educator. Seven months later and I’m switching gears; I’m just an educator that wants all kids, especially my black kids, to succeed.

Standardized Exams: Yes, they matter.

The National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE) published a story in 2003 about a midwestern teacher who was concerned with the “quality of fiction” that her 3rd graders were producing. Lee, a “whole language” teacher turned to Lucy Calkins’ pedagogy to teach personal writing. The purpose of writing was to expose kids to social issues they cares most about and to develop “text participants” who construct meaning. My biggest question after reading this article was, “Can the students read and write proficiently in accordance with their grade level”? Research suggest no.

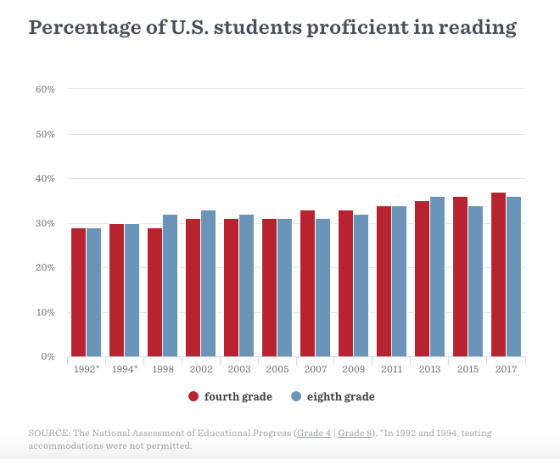

Senior education correspondent Emily Hanford wrote that according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, “More than 60 percent of American fourth-graders are not proficient readers… and it’s been that way since testing began in the 1990s.” (APM) . This marks almost 30 years where nothing has changed for our students.

We have to stop making excuses for why our students aren’t experiencing academic success. The issues our students face such as high mobility, poverty, and the like give us context for when we

teach them, but they do not absolves us of the responsibility to teach them in an equitable way. If you do make excuses and have low expectations, that too, is racism.

This argument dates back to the reading wars of “whole-language” instruction versus phonics and continues into secondary grades with workshop models and project-based learning.

Here’s the truth: Our kids can’t read, and it’s been that way for far too long.

So-called Struggling Readers: Stop Treating the Symptoms

By middle school, students:

- are assumed to be proficient readers (4)

- have likely experience for years of failure resulting in lack of practice, low fluency, and lagging decoding skills (6)

- Are spending more and more time online and less with traditional forms of media like books, magazines, and even television (5)

“Think about how difficult it must be to read even five pages of an 800-page college textbook when you’ve been used to spending most of your time switching between one digital activity and another in a matter of seconds”.

Jean M. Twenge in “Teens Today Spend More Time on Digital Media, Less Time Reading”

Given that in digital environments, texts are less likely to have “traditional features like text structure, organization signaling, headings, subheadings and the like”(1), not only are our students reading less outside of class, they also are encountering less traditional writing. As a result, these students are not developing circuits in their brain that allow for deep reading and Maryanne Wolf, author of Reader, Come Home warns that the quality of their attention is changing. Students’ brain plasticity coupled with lagging decoding skills ensures they can only read short blurbs or those accompanied by pictures (such as graphic novels) as they can only read for the gist. They are less able to dive deep into the discussion of how the words, phrases, and ideas connect in our brain. They are not developing the “slower” and essential cognitive processes such as critical thinking, reflection, and empathy (10). Teachers are instead expected to bring these alternative texts into our classrooms, and adapt to the so-called new brains of our students.

At some point in the last 30 or so years, we concluded that kids aren’t reading not because they can’t, but because they only want to read about what interests them– we let growing adolescents choose what’s fun rather showing them something new and giving them access to a world of knowledge and perspectives. We chose meaning, and subsequently, their failure over mastery.

Balanced literacy and Reader’s/Writer’s workshop both credit student engagement/interest as the cause of low test results, but their curricula have been unsuccessful in bridging the gap between students of color and their white counterparts. So, maybe it’s time to look at the quality of our curriculum and instructional methods.

Toward a Model of Culturally Relevant Direct Instruction

The best outcomes for students involve a setting where they can experience academic success and see themselves as a part of the world. This involves combining two frameworks:

Direct Instruction “is based on the theory that clear instruction eliminating misinterpretations greatly accelerates learning for all students. Over 40 years of research has proven that DI dramatically increases academic performance of students of all backgrounds” (National Institute for Direct Instruction).

Culturally relevant pedagogy was introduced by Gloria Ladson-Billings in 1995 and it has three main requirements for students. They must:

- experience academic success which includes basic skills like literacy and numeracy

- develop and maintain cultural competence as schools remain alien and hostile place for kids of color

- Develop the ability to analyze the status quo

I offer that the pedagogical framework of Ladson-Billings coupled with the instructional methods outlined in DI would be the best way of addressing the skills gaps in the 70% of students who can’t read (and by extension, write) proficiently. You can both “read the world” as Paulo Freire puts it, and read the word. What matters is how we sequence the curriculum so that students have the necessary skills and content knowledge to be able to engage in more of the inquiry-based learning later on.

In a previous post, I called for a balance of direct instruction and inquiry learning because excluding either one from curriculum perpetuates inequity in some way– either through its exclusionary view of knowledge as primarily western or very little direct instruction in addressing skill gaps. In that post, I didn’t know what that balance would look like. A week or so later, I came across Tom Sherrington’s blog where he outlines what he calls “Mode A: Mode B” teaching.

The most compelling piece from this post is the approach Sherrington takes to prioritize students learning and success, and which has informed my teaching philosophy:

“I can’t imagine a truly great curriculum where students do not, at some point, have a range of hands-on experiences, learn to make choices, explore ideas independently to find patterns and rules or develop original ideas. They need to have the chance to make things, to work with each other and to pursue some areas of the curriculum in an extended fashion through projects. It’s just a question of these things being sequenced and structured well so that the learning builds on secure foundations”.

This balance is rooted in principles of Direct Instruction of which the ultimate aim is mastery (and it has years of research supporting the practices).

Without neglecting Ladson-Billings’ first tenant of academic success, we can combine the mastery focus of Direct Instruction and within that sequenced curriculum, ensure that the knowledge students walk away with is culturally relevant and allows them to interrogate the status quo.

This would at minimum require

- a year-long knowledge map outlining vocabulary words, key concepts, content knowledge (possibly in the form of time periods)

- Rigorous literacy instruction as outlined in Doug Lemov’s “Reading Reconsidered”

- An acknowledgement of language arts as a body of knowledge rather than transferable isolated skills.

- Careful selection and balance of critical fictions or fictions to read critically (bell hooks)

This is my vision and hope for what my classroom could be next year.

Conclusion

The left has taken on a white-savior mentality masked in a misreading of Freire’s pedagogy and young adult literature. The traditionalist right has been categorized as being “steeped in the whiteness of education reform” due to their conception of knowledge. Gloria Ladson-Billings and the principles of Direct Instruction both have the answers– we just need to combine the approach, root our methods in research, and tailor it to our students.

I also realize that despite my few years of running after-school literacy programs, summer teaching fellowship, and work in charter schools, next year will still be the first time with my own classroom.

This is what I believe:

- You can’t solely focus on equity in terms of test scores. If you do, you entertain the (strong) possibility of graduating students that have no sense of self, reinforce the status quo, and perpetuate white supremacy (aka, me 5 years ago).

- Direct instruction is the best way to fill in the gaps for our students. You can’t propagate junk-science or ignore research. Test scores do not mean everything, but they do mean something. Only those that have never had to worry about passing standardized exams have the privilege to say that tests don’t matter.

So, this upcoming term (and summer), I’ll be developing my curriculum and focusing on finding a school that supports my vision for students– in Minnesota, or elsewhere.

I’m on twitter @MsJasmineMN

Further Reading

- Beach, Richard, and David G. OBrien. Using Apps for Learning across the Curriculum: a Literacy-Based Framework and Guide. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015.

- Hard Words: Why American Kids Aren’t Being Taught to Read

- Hefferman, Lee, and Mitzi Lewison. “Social Narrative Writing: (Re)Contructing Kid Culture in the Writer’s Workshop.” NCTE Comprehensive News, http://www.ncte.org/journals/la/issues/v80-6.

- Learning to Read to Learn

- Teens Today Spend More Time on Digital Media, Less Time Reading

- Obrien, David, et al. “‘Struggling’ Middle Schoolers: Engagement and Literate Competence in a Reading Writing Intervention Class.” Reading Psychology, vol. 28, no. 1, 2007, pp. 51–73

- Rothstein, Andrew, et al. Writing as Learning: a Content-Based Approach. Corwin Press, 2007.

- Trends in U.S. Adolescents’ Media Use, 1976–2016: The Rise of Digital Media, the Decline of TV, and the (Near) Demise of Print

- Why Millions of Kids Can’t Read and What Better Teaching Can Do About It

- Wolf, Maryanne. Reader, Come Home. HarperCollins, 2018.

[…] post was written by Jasmine Lane and originally ran on her Ms. Jasmine Blog. You can follow her on twitter […]

LikeLike

I love this blog. Used Direct Instruction 45 years ago with my first grade, mostly minority, low-income class (because the entire school used it). At the end of the year, all of my students could decode at grade level, some above grade level. And there was time for me to read great stories to the children.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! A common issue that people comes with DI is that it takes away the “fun” from learning. On the contrary, it gives students the ability to actively engage in their learning with support from a dedicated teacher– which I argue, is fun! I also love reading/studying books as a whole class. It was my favorite part of my schooling experience.

LikeLike

[…] time that instruction starts to focus on reading to learn rather than teaching students to read (if they are really taught at all). Did Miguel ever learn his sílabas in English? My guess is, probably not. Rubinstein-Ávila notes […]

LikeLike

[…] doesn’t have to be either-or; you can (and should!) have a curriculum that ensures both to work toward what I call a model of culturally relevant direct instruction. If we, as educators, claim that we care about our students, we can not leave their success to […]

LikeLike

I love your conclusion and the rejection of the savior mentality among far too many White teachers. Also, bravo for your endorsement of direct instruction. Great blog post. 👏🏾

LikeLike

[…] post was written by Jasmine Lane and originally ran on her Ms. Jasmine Blog. You can follow her on twitter […]

LikeLike

[…] families can provide a home environment that greatly enriches their background knowledge, and thus their future success. All children can be made more academically successful by systematically and purposefully enriching […]

LikeLike

[…] the very worst schools, we cannot pretend these tests don’t matter. To quote Jasmine Lane, “Only those that have never had to worry about passing standardized exams have the privilege to say t… So yes, I test my […]

LikeLike

You have an incredible future ahead of you. This is a sound program. I have taught DI with more than one program, and I know how well it works when done with both enthusiasm and fidelity. I love the inclusion of a component that allows for passion. This was always the missing piece to keep the students engaged. Simply allowing them to choose “interesting” books was not enough. Students have to be roped in wholeheartedly to their special interest and then they will turn to reading in order to learn.

I look forward to more interesting writing from you. Find a place that will allow you to explore these ideas with your classes and colleagues and will cherish your value and worth. Stay in the classroom for a little while before getting that next degree and moving up.

Marge

LikeLike